Examples

This page is a collection of examples, meant for learning and explaining the language Ampersand. TODO: refactor this documentation to match the latest syntax.

Example: Multiple files

This example illustrates how an Ampersand specification can consist of multiple files.

In this example, we have two files. File foo.adl contains the following text:

CONTEXT MultifileDemo

INCLUDE "bar.adl"

RELATION r[A*B]

RULE r |- s

ENDCONTEXT

and file bar.adl contains:

CONTEXT MultifileDemo

INCLUDE "bar.adl"

RELATION s[A*B]

ENDCONTEXT

Without the INCLUDE statement, file foo.adl does not compile because relation s is undefined.

The INCLUDE statement causes all definitions of bar.adl to be included in the context of foo.adl, so this example compiles without errors.

Example: Client

This example illustrates the structure of interfaces in Ampersand

A Client interface

Suppose we have a delivery-hub that distributes orders over vendors and registers the subsequent deliveries. Let us define an interface for clients, to allow clients to change their name and address and display their orders.

INTERFACE ClientInfo FOR Client,Vendor : I[Client]

BOX [ "Name" : clientName

, "Street" : clientAddress

, "City" : clientCity

, "All orders" : orderedBy~

BOX [ vendor :orderedAt

, product : orderOf

]

, "Orders to be accepted by provider" : orderedBy~ - V;orderAccepted~

, "Orders pending delivery" : orderedBy~ /\ (V;orderAccepted~ - orderReceived~)

, "Received orders" : orderReceived~

]

Structure

The interface has a header, which is the first line in this example:

INTERFACE ClientInfo FOR Client,Vendor : I[Client]

The word ClientInfo is the name of this interface. This name identifies the interface , so it must be unique throughout the entire context.

This interface is shown only to users with roles Client or Vendor. That is indicated by the restriction FOR Client,Vendor. Without that restriction, the interface is available for every user in any role.

The term to the right of the colon (:) symbol is called the interface term. An interface is called from an atom which must be in the domain of this term. Let, for example, Peter be a Client. As Peter is an element of the domain of I[Client], the interface can be called from that atom.

The same term, I[Client], is also used as box term for the box that follows the header. For every element in the codomain of the box term, a container (in HTML: <div>) will be drawn on the user screen. That box serves as a subinterface, which is called with precisely one atom. With I[Client] as box term, the codomain will contain just one atom, which is precisely the atom from which the interface was called.

In this example, the outermost box contains seven box items and the innermost box two. Each box item has a label and an term. For example the box item "Name" : clientName has "Name" as its label and clientName as term. The atom a from which the box was called is used to select the pairs (a,x) from the term. All x-es for which (a,x) is in clientName will be displayed. Supposing that the relation clientName associates only one name to a client, this specific box item displays just one name. However, in the fifth box item, the term orderedBy~ - V; orderAccepted~ may contain an arbitrary number of orders to be accepted by provider, all of which are shown.

description: 'TODO: This example is subject to bitrot. It has to be redone.'

Example: Login

This example defines a login/logout interface,

because it is familiar. We show this example to demonstrate how to get different interface structures under varying conditions.

Preliminaries

The compiler uses templates to adapt an interface to specific needs regarding its HTML structure. Please read the documentation of templates first for details.

To link system activities to a person or organisation, we use the notion of Account. To log in means to associate a session with the Account of the user. This association is made in the relation sessionAccount. To log out means to break that link, i.e. to remove the session/account pair from relation sessionAccount. When logging in, it is customary that the user identifies herself. In this example we do this with a UserID and Password.

A UserId is used to identify the user by a unique name. In this way, the (system generated) key of the user in the database is kept within the database.

To make it more difficult to use an other person's Account, the system registers passwords. A Password is a string of characters known to the user only. For this reason, the login interface must not expose the password while the user is typing it.

To isolate a data space for one specific user, we use the notion of session. A SESSION corresponds with the notion of session as used in browsers. Ampersand links the session called '_SESSION' to the current browser session, which results in the behaviour one would expect of a browser session.

How the interface works

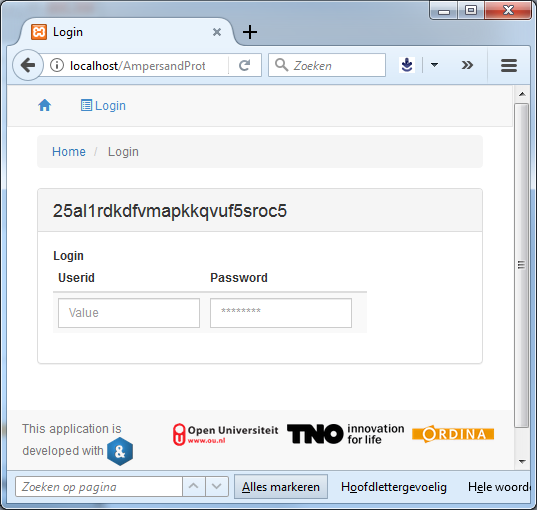

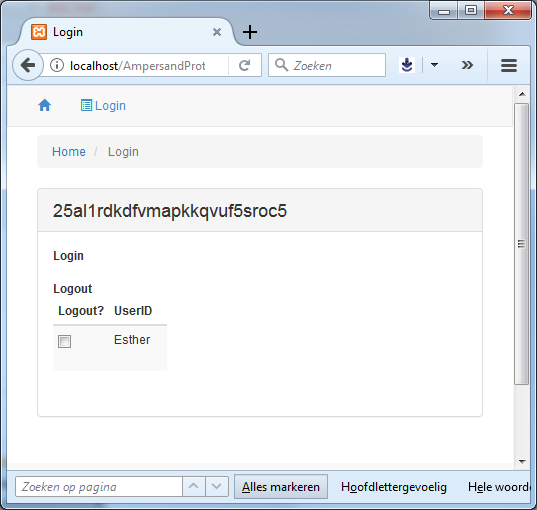

A login interface allows a user to log in and log out of the system. Here is what it looks like in a browser:

Wonder what the 25al1rdkdfvmapkkqvuf5sroc5 means? Well this is the session number of the actual browser session. It is the value for which the atom

"_SESSION"

stands in your script.

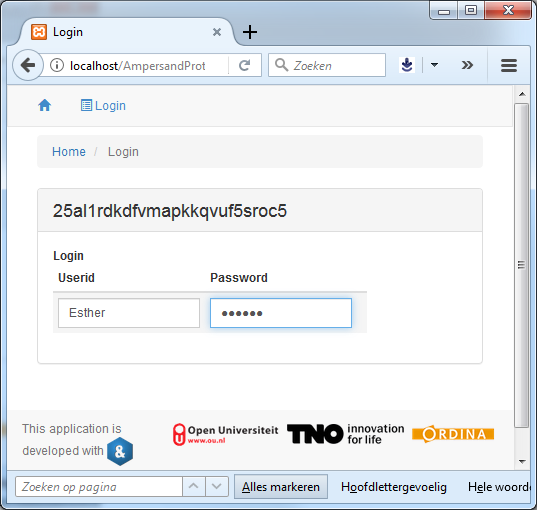

When you type your name, it shows up in the field Userid, but when you type in the password it is obscured by dots

(

as we would expect

)

:

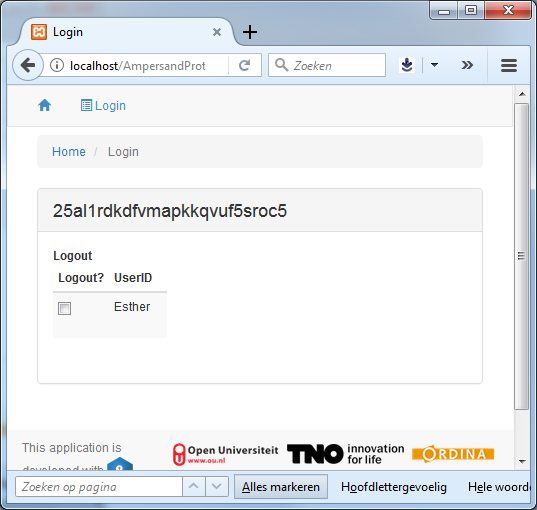

When we then type

<enter>

, the login functionality disappears and the logout functionality appears:

When you click the checkbox, you have logged out and will return to the first screen

What the Ampersand code looks like

To understand how it all works, let us discuss the code for this interface:

INTERFACE Login : '_SESSION'[SESSION] cRud BOX <HROWS>

[ "Login": I - sessionAccount;sessionAccount~ cRud BOX <HCOLS>

[ "Userid" : loginUserid cRUd

, "Password": loginPassword crUd -- crUd is needed for Passwords

]

, "Logout": I /\ sessionAccount;sessionAccount~ cRud BOX <ROWSNL>

[ "Logout": I cRud BOX <HCOLS>

[ "Logout?": logoutRequest cRUd

, "UserID": sessionUserid cRud

]

]

]

If you analyse this code, notice the nested structure of BOX-es. The interface is a box on the top level with two sub-boxes labeled "Login" and "Logout".

The top-level box has "_SESSION"[SESSION] as its box-term. What you must remember is that the every atom of the codomain of that term causes one contain (HTML: <div>). In this example, the codomain of "_SESSION"[SESSION] is just one atom, which is the session identifier. That is shown in the title of the outmost box in the browser.

Selectively showing subboxes by <HROWS>

We would expect to see two subboxes, one labeled "Login" and another labeled "Logout". However, the outmost box was annotated with <HROWS>. The H stands for hidden. It means that empty subboxes will be hidden from the user. Now look at the box-terms of the "Login"- and "Logout" subboxes. Which elements are in the codomain of the box-term of the "Login" subbox? It says: "All sessions without an account associated with it". Since there is only one session (i.e. the browser-session) this comes down to "the current session, provided there is no account associated with it." So if nobody is logged in in the current browser session, the session atom is the only atom. Otherwise there is no atom and the "Login" subbox is not shown. Similarly, which elements are there to make the the "Logout" subbox appear? That box-term shows all sessions associated with an account. Which would be the account of the current session, provided someone is logged in.

That explains why the "Login" subbox is shown when nobody is logged in and the "Logout" subbox is shown when someone is logged in.

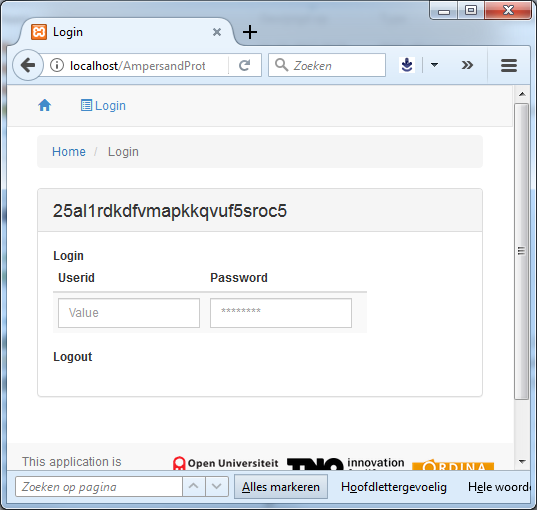

So let us do the following experiment: change the

<HROWS>

annotation to

<ROWS>

. Then we will see both boxes:

Notice that both subboxes have the

H

in their annotations, so in the screeshot above the

"Logout"

subbox remains empty. However, when logged in, the other subbox remains empty:

Example

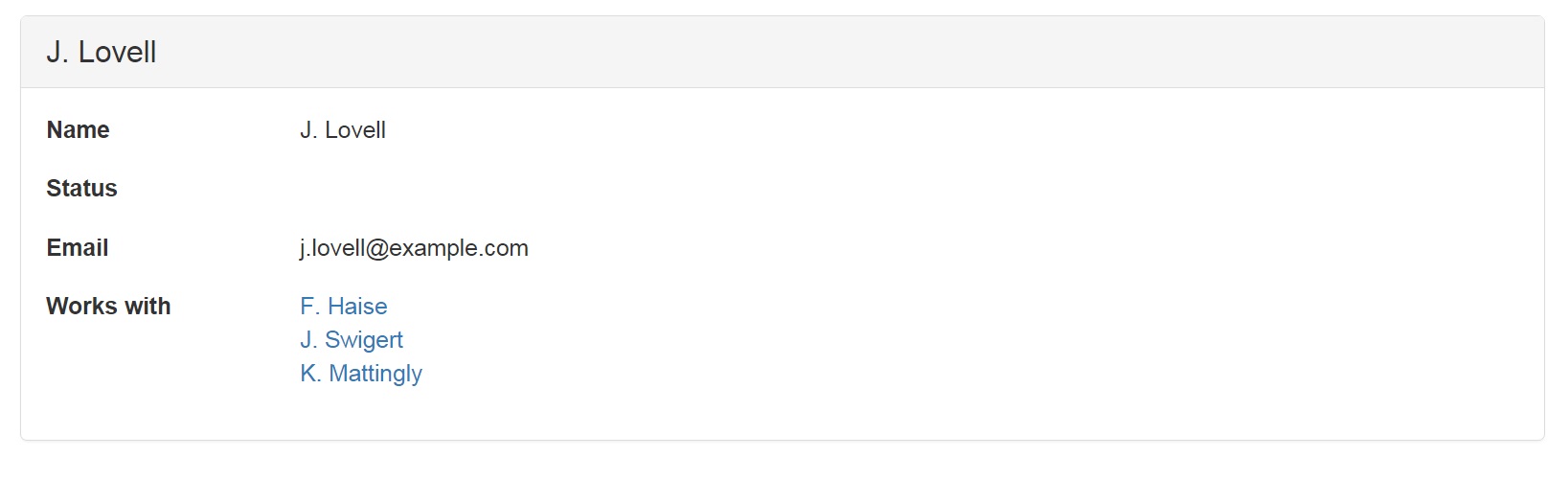

To understand the structure of an interface (keyword: INTERFACE), this section introduces a small example of a user interface, which shows the name, status, e-mail and co-workers of a person called "J. Lovell".

The specification of this user interface is given in the following interface definition:

INTERFACE Person : I[Person]

BOX

[ "Name" : personName

, "Status" : personStatus

, "Email" : personEmail

, "Works with" : workswith

]

To understand this fragment, take notice of:

The name of this interface is

Person. This name immediately follows the keywordINTERFACE.The term following the colon,

I[Person], is the interface term of this interface.The interface can be applied to any atom from the domain of the interface term. So this particular interface is applicable to any atom of type

Person. In the screenshot, it applies to"J. Lovell".The labels "Name", "Status", "Email", and "Works with" correspond to field names in the user interface.

Each term at the right of a field name specifies which data is presented in the field. For this reason it is called the field term for that field. Field name and field term are separated by a colon.

Of all pairs

<"J. Lovell", x>from the field term, the field displays the right atomx. A field term always works on one specific atom on the left, which is"J. Lovell"in this example.Field terms are subject to type checking. The following relations provide an example for getting a type-correct interface:

RELATION personName :: Person * PersonName [UNI]

RELATION personStatus :: Person * PersonStatus [UNI]

RELATION personEmail :: Person * Email [UNI,TOT]

RELATION workswith :: Person * PersonThe source concepts of a field term must match the target concept of the interface term.

Looking at the screenshot, we can tell that

"J. Lovell"has one personName (which is"J. Lovell"), it has no personStatus, one personEmail and three persons to work with inRELATION workswith.

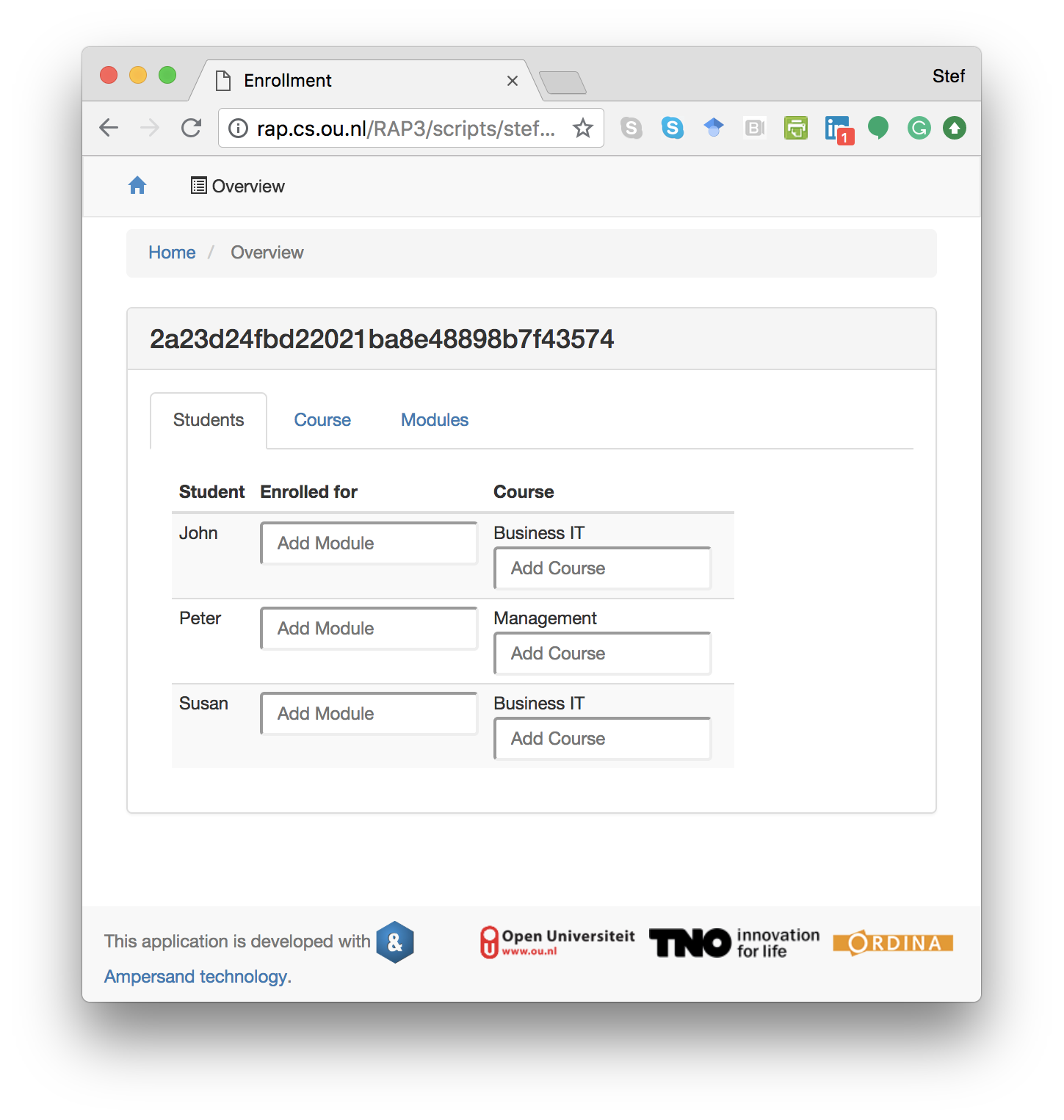

Example of an interface

INTERFACE Overview : "_SESSION" cRud

BOX <TABS>

[ Students : V[SESSION*Student] cRuD

BOX <TABLE>

[ "Student" : I[Student] cRud

, "Enrolled for" : isEnrolledFor cRUD

, "Course" : takes CRUD

]

, Course : V[SESSION*Course] cRuD

BOX <TABLE>

[ "Course" : I cRud

, "Modules" : isPartOf~ CRUD

]

, Modules : V[SESSION*Module] cRud

BOX <TABLE>

[ "Modules" : I cRuD

, "Course" : isPartOf cRUd

, "Students" : isEnrolledFor~ CRUD

]

]

This example specifies three tabs. One shows students, one shows courses and one shows modules. This is what it looks like when run in a browser:

Notice the following features:

- The structure of an interface is hierarchical. It consists of boxes within a box. This is because a field term may be followed by a

BOXwith a list of subinterfaces. Without it, it is just a field term. - When a field term is followed by a

BOX, every atom in the codomain of the field term is displayed in a box of its own on the screen. That box behaves like an interface with the field term serving as interface term of that subinterface. - By this mechanism, the hierarchical structure of the entire interface translates directly to the hierarchical structure of the web-page in which it is displayed.

- The source concept of a field term must match with the target concept of the field term outside the box.

- The target concept of a field term that has a box, must match with the source concepts of each field inside that box.